Allison’s Final Paper

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on December 9, 2009

Allison for Nov. 17

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on November 15, 2009

Aside from their alliterative “W” names, Walt Whitman and William Carlos Williams have a lot in common. I’m surprised and slightly disappointed in myself for not seeing the heavy Whitmanic influence over Williams’ work before. Both WWs have held consistent spots in my “top 5” since high school, and now I feel an entirely new level of intimacy with these two poets as we enter into some kind of weird poetic-connection-triangle. After reading Higgins article, I read through some of Williams’ poems that I had read before and saw them differently than I did years ago (way back when Whitman was just a poet I liked and not a sea of multitudes in which I am completely and constantly submerged). It’s official, I am now equipped with Whitman-Tinted Glasses.

Poetically, both (1855-1860) Whitman and (1940s-1950s) Williams’ focus on the elemental self, the particulars, the details, the Romantic, and the beautiful. The reader looks through the poem as a microscope, narrowing in on individual blades of grass rather than an entire field or lawn:

“And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves” (Whitman 31).

“The file sharp grass… and a grasshopper of red basalt, boot-long” (Williams 277).

These lines, like many others, could be inserted interchangeably into Whitman’s or Williams’ poems without any break in poetic style, form, or content. Williams even riffs on Whitman’s parenthetical asides, inserting his own voice and creating the same intimacy that Whitman achieves in his poetry. Take for instance this side comment in Williams’ “The Delineaments of the Giants”:

“The river comes pouring in above the city

And crashes from the edge of the gorge

In a recoil of spray and rainbow mists—

(What common language to unravel?

. . combed into straight lines

from that rafter of a rock’s lip.)

A man like a city and a woman like a flower…” (262).

This follows typical Whitmanic formula. First, the depiction of beautiful and powerful nature—I don’t think I need to remind you of all the instances of the sea, ocean, and rivers in Whitman’s poetry. The parenthetical aside that follows questions the metaphysical underpinning and muses on the deeper meaning of the previous image (not to mention the classic 1855 Whitmanic ellipsis thrown in there as well). Lastly, Williams’ makes the move from natural world to humanity, equalizing the beauty of Man to that of the previous “rainbow mists.” If I didn’t already know this passage was from a Williams’ poem, I would have confidently identified Whitman as the author. If the similar structure and subject matter isn’t enough to confuse you, Whitman and Williams even make similar word choices in their poetry. Each combines fluid, aesthetic, and relatively simple words with a more sophisticated, Latinate vocabulary. Despite all these similarities in Williams’ work to Whitman’s, Williams’ is far from a copy cat.

The most significant parallelism between Whitman and Williams is how their rare and innovative existence within their own times. Both poets seem to come from nowhere, creating poetry the likes of which their contemporaries had never seen before. The 1855 Leaves of Grass was a non sequitur amongst mid-19th century poetry and planted the seed for poetic trends to follow, most importantly the use of free verse as the official “American” poetic style. Like Whitman, William Carlos Williams served as a poetic catalyst for the imagist movement in the early 20th century (see: “The Red Wheelbarrow”). He even invented what became known as the variable foot, which is based off the condensed and simplified linguistic trends Williams’ observed in American society, i.e. newspaper headlines and radio announcements. Like Whitman’s innovations, Williams’ stylistic influence can be seen decades later (See: Jane Hirshfield’s “Red Scarf”). Even though Whitman preceded Williams, both poets contribute their own unique layer to the ancient and ever-changing poetic palimpsest (shout out to Dr. Scanlon!).

With all that in mind, what I find more impressive about Whitman’s legacy as opposed to Williams’ is the sheer number of writers who mimicked Whitman in one way or another. In Higgins article, it’s almost like Whitman is more than one man. Whitman’s work contains such multitudes that he has produced several legacies. William Carlos Williams may mirror the individualistic Whitman, but Pablo Neruda channels Whitman’s idea of “en-masse,” and T.S. Eliot evokes Whitman by being the Anti-Whitman. This is perhaps the most impressive aspect of Whitman, that even post-mortem he contains multitudes.

Finding Whitman Project

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on November 13, 2009

*Wardrobe provided by the University of Mary Washington.

Allison for Nov. 10

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on November 8, 2009

There has been a shift in the way I read and relate to Whitman. In the 1855 edition, Whitman felt like my pal; his messiness, his unbridled passion, his desire to explore everything and know everything, his embrace of his own egotism—all these things I relate to as a twenty-something. While reading the deathbed edition of Leaves, however, I couldn’t help the feeling that I had become Walt’s daughter / granddaughter, or student. Instead of focusing on mere aspects of life, Whitman reflects on life as whole. He bestows his “words of wisdom” to his readers in succinct, almost adage-like poems. With the 1891-1892 Leaves of Grass, I have found my Papa Walt.

I am beside myself with excitement to finally be able to discuss my favorite Walt Whitman poem of all time. O Me! O Life! is the perfect example of Papa Walt’s wisdom. Many of you might remember this scene from the movie Dead Poets Society, in which Robin Williams’ character uses this poem (abbreviated in the movie) to inspire teenage boys to study poetry. Papa Walt would have approved of this, because within the poem he presents a student/teacher dialogue.

The poem is divided into two parts with two different speakers: the first is spoken by the student/ the son / the youth, followed by a response by the answerer / the teacher / the father figure. The youth questions what is the “good” of life when it’s often filled with foolish and faithless people, and daily routines and struggles forever renewed; to which the older and wiser speaker responds calmly:

“That you are here—that life exists and identity,

That the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse” (410).

The first speaker speaks from the thick of life, whereas the second speaker comes from a more objective point of view—as one “beyond” life. Not that the second speaker is a ghost, but rather someone who has experienced and come out the other side of what the first speaker recounts. Even though the answerer is older and wiser, they give value to the questioner. By responding with the direct address “you,” the second speaker emphasizes the first speaker’s importance in the large, consuming world.

This poem could also be read as Papa Walt’s address to his former, younger self. The first section mirrors his 1855 writing style with its many “O”s, exclamation and question marks, repeated line beginnings, and verbose detail; whereas the answer portion is short, “seriously” punctuated,” and makes a broader statement, all of which are tell-tale signs of the more mature Walt Whitman. While the younger Walt zeros in on specificities and uses many words to do so, Papa Walt squeezes more profundity into fewer words (notice how Walt’s shorter poems do not emerge until after 1855). Within this one poem, Whitman reflects on his current and former self, and many “verses” he has contributed.

Though there is a greater focus on death in the 1891-1892 edition of Leaves, which is, of course, sad, there is still a sense of optimism in Whitman’s writing. There is never death without the reflection on life. Even his most morbid poems like The Last Invocation, Life and Death, and Good-Bye my Fancy! include reflections on love, the soul, and life. Papa Walt inspires us in his old age to live a life as full and passionate as his own. And Papa Walt knows what’s best.

“O I see life is not short, but immeasurably long,

I henceforth tread the world chaste, temperate, an early riser, a steady grower,

Every hour the semen of centuries, and still of centuries.

I must follow up these continual lessons of the air, water, earth,

I perceive I have no time to lose” (380).

Allison for Nov. 3

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on October 31, 2009

What lurks behind editing?

We know now a great deal about his personal life through his letters, Memoranda, information given to us by our pals Reynolds, Morris, and Erkkila, but there still remains a void. Whitman, containing multitudes, is not easily pieced together. His poetry, though we can only speculate, reveals some thing deeper than biographical information. Through the evolution of his poems, we see the evolution of the man himself– an edited poem flows from an edited mind. Song of Myself, even within its title, serves as Whitman’s mirror, and the changes that occur within the poem over 36 years reveal much about the mindset of our beloved poet not long before his death. What was even more revealing to me, however, were not the things that changed over three decades, but what stayed the same.

Within the first stanza of the 1891 version of Song of Myself, Whitman immediately makes an edit, reminding the reader that this is a different poem from a different man:

“My tongue, every atom of blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here of parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death” (188).

Whitman was, of course, not thirty-seven years old when he made this revision. Instead he reminds us of from where and who the poem originates; Song of Myself is birthed from vitality, from youth, and not from the current state of the writer at the time (nearing death). With the following line, Whitman links his thirty-seven year old self with his current self, knowing that he has achieved the “hope” of his younger self. With this, Whitman re-writes Song of Myself reflectively, and we read it reflectively. Whitman desires and challenges the reader to see the meaning behind his editing.

We have discussed at length the concept of “en masse” and its significance to Whitman, i.e. his philosophy of the American identity, unity through diversity, and comradeship, and it’s no surprise that “en masse” has become capitalized (literally) in Whitman’s writing after 36 years of theorizing it. Along with the capitalization, Whitman describes “En-Masse” as, “without flaw, it alone rounds and completes all, / that mystic baffling wonder along completes all” (210); whereas in 1855, he defines “en-masse” as, “a word of the faith that never balks,/ One time as good as another time…. here or henceforth it is all the same to me” (49). His attitude towards “En-Masse” shifts from a favorable, yet semi-apathetic one, to something he exaggerates passionately about. Whitman couples “En-Masse” with a thought on reality. In 1855 he submits a “word of reality” (49), and in 1891 he “accepts Reality and dare not question it” (210). Reality, capitalized like En-Masse, has become a force worth recognition, something he must submit to; for Whitman to set aside something (anything!) that he will not question, reveals the reverence he has developed for Reality. We, of course, know the reality that Whitman will meet one year later.

Despite the fact that Whitman is ailing in 1891 and nearing death, he maintains his optimistic, almost flippant, remarks about death. The 1891 SOM asserts, just as the 1855 version, that life springs from death, that death is nothing to fear: “And as to you death, and you bitter hug of mortality… it is idle to try to alarm me” (85 and 245). The only difference within these lines about death is that in 1891 “death” is capitalized, as are “corpse” and “life.” So though Whitman maintains his same theory about life and death, but in 1891he pays more respect to their significance and presence. Some lines, however, do not change at all, not even in syntax or punctuation. Most notable of the unchanged lines are the very last 8 lines of the poem. At age 37 and at age 73, Whitman chooses to end his poem with the same enigmatic, enduring words. No matter his age, we will find him under our boot-soles.

Whitman’s “Recycled” Words

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on October 30, 2009

Quick post about an observation that just occurred to me. I was just reading the Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass and I stumbled across these little nuggets:

“The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

and:

“Here is not merely a nation but a teeming nation of nations.”

and:

‘Here is action united from strings necessarily blind to particulars and details magnificently moving in vast masses.”

and:

“Here are the roughs and beards and space and ruggedness and nonchalance that the soul loves.”

and:

“Here the performance disdaining the trivial unapproached in the tremendous audacity of its crowds and groupings and the push of its perspective spreads with crampless and flowing breadth and showers its prolific and splendid extravagance.”

After reading through these “heres”, I couldn’t shake this feeling that I had read this some where else. Check out this stanza from “By Blue Ontario’s Shore”(1856, 1881):

“These states are the amplest poem,

Here is not merely a nation but a teeming Nation of nations,

Here the doings of men correspond with the broadest doings of the day and night,

Here is what moves in magnificent masses careless of particulars,

Here are the roughs, beards, friendliness, combativeness, the soul loves,

Here the flowing trains, here the crowds, equality, diversity, the soul loves.”

The poem pulls, almost verbatim, from the preface. Can someone plagiarize them self? Fanny Fern does advise in her article “Borrowed Light” to find a great writer and copy their writings as closely as possible, perhaps Whitman is just followed her advice and selected himself as a great writer. What do you guys make of this? Any more examples of Walt’s “recycled” words?

Allison for Oct. 27

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on October 25, 2009

To express oneself so freely, so eloquently, and in such detail denotes someone who is self aware. Whitman is extremely self aware and fully capable of exploring and identifying the “multitudes” within himself. I believe this heightened sense of awareness, which borders on prophetic at times, is what attracts Whitman to Lincoln. Whitman is able to identify a kindred spirit in Lincoln, a man with a similar mind and equal greatness to himself. Lincoln, however, holds authority that Whitman recognizes he himself will never wield, but he respects and almost vicariously lives through Lincoln’s great influence. Simply put, Whitman would have made the same decisions as Lincoln if he had been elected President.

What unites the men is the “great Idea,” which Whitman refers to several times in “By Blue Ontario’s Shore.” Though Whitman states that the great Idea is the “mission of poets,” he defines the great Idea in national and political terms. First he places the great Idea within the context of war (it’s no mystery what war), then the great Idea becomes part of sweeping statement about unity and equality, and lastly he couples the bard of the great Idea with the bard of “peaceful inventions” (483). Here, Whitman hints the connection between a poet and a President; both the poet and the President, though one undoubtedly more powerful than the other, can have equally as great Ideas. He takes this poetical/political comparison one step further by asserting, “these States are the amplest poem” (471), describing the potential for great unity within the Nation, which was, of course, Lincoln’s primary objective. Similarly, both men look at the “Big Picture,” look toward the future, as motivation. Whitman writes, “O days of the future I believe in you” (474), which mirrors in a more concise, poetic way Lincoln’s closing words in the Gettysburg Address: “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government: of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Lincoln’s use of the future tense and words like “new birth” are no accident, both Whitman and Lincoln saw past the grim present and towards a brighter future, knowing well that the war was justified.

Though our Good Grey Poet most certainly felt connected with Lincoln, I doubt the two could have ever been friends; not because of their differing status in society, but because Walt Whitman placed Lincoln on a higher plane of existence than himself, almost deifying him. Countless times in both his poetry and prose, Whitman refers to Lincoln as a martyr, which perhaps he was, but Whitman elevates Lincoln’s martyrdom to hyperbolic, Christ-like proportions. In “This Dust Was Once The Man,” Whitman describes the South’s attempted succession from the Union as, “the foulest crime in history known in any land or age” (468), and that Lincoln saved, single-handedly, the Union from this most heinous injustice. Aside from the ridiculousness of the first assertion (I mean, come on, the Spanish Inquisition was much worse), Whitman has made Lincoln the savior of Union. Even in his assassination, something not of Lincoln’s control at all, Whitman paints Lincoln as the critical element in America’s identity. In his lecture Whitman drives this point home over and over again: “strange (is it not?) that battles, martyrs, agonies, blood, even assassination, should so condense– perhaps only really, lastingly condense– a Nationality” (1070). Lincoln, like Christ in Christianity, becomes the fountainhead of a new nation– the first great Martyr Chief, as Whitman calls him.

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to pinpoint the bond between Whitman and Lincoln. However, I think the love Whitman feels for him is far deeper than the “crush” we joke about in class (even though Whitman likes Lincoln’s tan face quite a bit). Whitman recognized that he himself was a great man and in Lincoln he saw another great man, and maybe that’s all there is to it.

D.C. Field Trip: My Grumpy Saga

Posted by cellatreis in Uncategorized on October 25, 2009

Quick Overview:

- Yesterday I left my house at 10am and did not return until 9:30pm.

- Rain.

- Wind.

- Lots of walking.

- Exhaustion.

- Grumpiness.

- Nap in Ford’s Theater.

- Library of Congress was awesome.

At 11am we began our walking tour that took us around to the places that Walt Whitman worked at and wrote about, i.e. The U.S. Treasury Building (formerly the Attorney General’s Office where Walt Worked), The Willard Hotel (where Walt occasionally visited and now there hangs a sketch of him in the bar), and The White House and Ford’s Theater (feeding into Walt’s super-man-crush on Lincoln). The highlight of the walking tour, at least for me, was Walt Whitman Way, which is between 7th and 8th streets on F. This is where Walt worked at the Patent Office (now the Smithsonian Portrait Gallery) and had previously tended to soldiers in this same building, and also lived in various boarding houses around the same area.

This image is from flickr, and most certainly not taken the day we were there– note the blue sky.

After a lunch break, we all went to Ford’s Theater. At this time I was at the precipice of grumpiness and tiredness. Here’s a brief overview of what interested me:

- John Wilkes Booth’s actual gun used to assassinate Lincoln.

- The Ranger who spoke to us looked like Drew Carey.

- The inside of my eyelids.

And that’s all I got.

Then, lots more walking in the rain. A quick trip into the Starbucks that used to be Alexander Gardner’s daguerreotype studio (shout out to Matthew Brady!) and then on to The Library of Congress. Here’s where I, and it seemed like everyone else, came alive.

HOW FREAKIN’ COOL!

To see the actual sheets of paper with Walt’s handwriting scrawled on it, his little edits in the margins, to see his letters the same way his recipients saw them– amazing! Of course, the piece de resistance was Whitman’s leather messenger bag, now falling apart and preserved in a special box, revealed to a crowd of gaping mouths, sounds of shock, and a couple sets of teary eyes. Plenty of pictures to come of this bag, we were like the paparazzi catching sight of Paris Hilton with that thing. It was truly incredible to see what the Library of Congress has preserved: locks of both Peter Doyle’s and Whitman’s hair, George Whitman’s small diary, Whitman’s journals from the hospitals, Whitman’s eye glasses, his cane, his pen, a cast of his hand, and lots more. It was overwhelming. Sam Protich, at some point, said excitedly, “this is awesome! Who gets to study like this?!” And of all the many intelligent, insightful, some times long winded, comments I have heard Sam make, this one is the most profound to me.

I’ll admit that I complain about my “Walt Whitman Class” all the time, to the extent that my friends call him my “Needy Boyfriend” because I spend so much time “doing” him, but I’m going to keep it real for a second: I love this class. Yes, it’s a lot of work. Yes, I was extremely tried, cold, hungry, and grumpy during our field trip. However, walking away from the Library of Congress, I felt good. I felt enriched. This class is not only worth my tuition money, but worth my time and mental vigor. I am actually learning. And I like it.

Reflecting on this feeling of “good” and enrichment, my mind was drawn to Paulo Freire’s essay “The Banking Concept of Education” (shout out to Jim Groom). Freire’s essay describes how limiting education can be, how the teacher/professor can fall into a pattern of narration, while the students become “containers” that mechanically memorize facts and promptly forget them after spewing them out on a test: “Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor.” This, sadly, is the mode of education that is most familiar to us. However, this course breaks that mold, nay it shatters it! What we have developed in this class is what Freire calls “authentic thinking,” which, “does not take place in ivory tower isolation, but only in communication.” Communication is our middle name; in class, students are speaking 80%-90% of the time. We are physically connecting to what we’re learning about. Instead of mindlessly “consuming” Whitman’s letters, we went out and saw them, were inches away from them. The reason we all feel personally connected to Walt Whitman is because he has become more than information and we have become more than “containers.” This is what it feels like to be a student.

Along with their comments about Whitman being my boyfriend, my friends will joke, “wow, you’re going to be, like, an expert on Whitman by the end of this semester.” To which I respond (not-jokingly), “yeah. I f–in’ will.”

Material Culture Museum: Ice Cream!

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on October 19, 2009

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

The origins of ice cream are mysterious. There’s documentation of people flavoring snow hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, but that’s really more of a primative snow cone than ice cream. Some might place its beginning during the reign of Nero (54-68 CE), because the famous Emperor enjoyed a frozen, sweetened combination of ice and fruit pulp, but of course that’s technically sherbet, not ice cream (Powell 12). Sherbet and other iced treats were around Europe for centuries until slowly emerged the addition of cream to the mixture. No one person is attributed to this discovery, but the first official recipe for ice cream was published by Nicholas Lemery in 1674 (Powell 26). By 1768, according to ice cream historian and expert, Marilyn Powell, the age of ice cream was under way (28).

But wait! Perhaps it’s not that simple and European! Myth has it that Marco Polo observed the Mongols making ice cream in China and then brought the recipe back with him to Italy. Though Marco Polo does not write explicitly of ice cream, he does, however, document drinking a fermented milk product called kumiss, which the T’ang rulers of China would enjoy mixed with rice and frozen. It seems as though the lines of this poem by Yang Wanli, c. 1200 BCE, describe ice cream:

It looks so greasy but still has crisp texture,

It appears congealed yet seems to float,

Like jade, it breaks at the bottom of the dish;

As with snow, it melts in the light of the sun.

(Powell 32).

There is, however, no concrete evidence of ice cream in China, nor are Marco Polo’s writings of China held in high regard (there are questions as to if he ever actually made it there). Where ever and how ever it emerged, ice cream did not truly “hit the scene” until the 18th century, and not long after gaining popularity in Europe, ice cream made the trans-Atlantic jump to the United States.

The Founding Fathers loved ice cream. While he was the ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson grew a bit of an obsession with ice cream, going as far as employing a chef in Paris who would make vanilla ice cream for him. Jefferson even created his own recipe for making vanilla ice cream, which actually does not even list vanilla as an ingredient (Powell 158). George Washington insisted on having ice cream on the White House menu, and years later Dolley Madison served it at the Inauguration dinner in 1813 (Powell 160). Don’t let these prominent white people fool you, the circulation and perpetuation of ice cream in American was solely because of African Americans. In fact, legend has it that Dolley Madison got her recipe for the Inauguration dinner from Aunt Sallie Shadd, a free black woman from Delaware who many believed to the “inventor” of ice cream. Augustus Jackson, a free black man, was a cook in the White House and after leaving his job there and moving to Philidelphia, began distributing his ice cream to street vendors, who were also mostly African American (Powell 161). These street vendors brought ice cream to the American public, often shouting slogans like, “I Scream Ice Cream” in 1828, which later morphed into, “I Scream, You Scream, We all Scream for ICE CREAM” in 1927 (Powell 162). Needless to say, by the time the Civil War began in 1861, ice cream had already been a part of the American diet for over 80 years and established itself as slogan-worthy treat.

Though Whitman had access to treats like ice cream and citrus fruits, these things were not prevalent during the Civil War. In her article, “Hard as the Hubs of Hell: Crackers in War,” Joy Santlofer discusses the diet of the Civil War soldier. Hard bread, or hard tack, was the staple food item during the war. This bread was so hard that it had to be shattered by a riffle or a sharp rock and then soaked in a liquid before eating, and more often than not, it housed maggots. This is what the soldiers ate every day. To break up the monotony of their diet, soldiers would add the hard bread to their coffee or stew (Santlofer 5). The reasoning behind this unfortunate diet was, of course, the lack of food preservation methods. The newest food technology was canning, sweetened condensed milk became a hot commodity amongst the soldiers (Santlofer 3). Canned food, dried and salted meats, and hard bread were primarily the only food items that could be kept and transported during the Civil War. So how was it possible for ice cream to exist in the summer heat of Virginia in the 1860s?

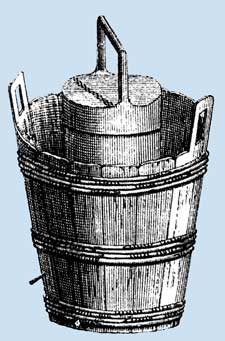

This question is not easily answered. Though there were forms of refrigeration by the 1860s, food preservation was still in its primitive stage. The ice box, literally an insulated box with a block of ice on the top shelf, were the most common in cold food storage. Though an ice box could store the cream and eggs used to make ice cream, it would have not been cold enough to store ice cream. A break through in food preservation was made in 1861 by Enoch Piper in Camden, Maine, when he patented a method of freezing a fish by coating it in ice and then moving it into an ice box with chilled brine of ice and salt (Rudi, “How We Got Frozen Food”). Of course we know that the addition of salt creates a lower temperature for various chemical reasons that no one cares to read about. Enoch Piper might have received the official patent for this discovery but this was already common knowledge to those making ice cream. Even in Thomas Jefferson’s recipe for ice cream, which I referenced earlier, instructs to layer salt with ice around the sabotiere. The ice cream was mixed in the sabotiere and left for a several hours in a combination of salt and ice to freeze before serving. Here’s an image that will help clarify– the sabotiere is the smaller container within the bucket, the empty space between the sabotiere and the bucket would have been filled with salt and ice.

www.historicfoods.com

It was common practice in the 19th century to place half-frozen ice cream, what we would call “soft serve” now, into a mold and then let the ice cream continue to freeze inside the mold (Powell 160). It’s doubtful this would have been done for the soldiers, however, because this was usually done for fancy dinner parties and special occasions. It is also unlikely that these reasonably sized sabotieres were used to feed an entire army. Here enters Jacob Fussell to save the day. Jacob Fussell established the first commercial ice cream plant in Baltimore in 1851, and supplied the Union troops with ice cream throughout the war by using refrigerated rail cars (Powell 163). Other smaller scale modes of ice cream production, i.e. making the ice cream on sight, were also used to feed the soldiers, but Fussell’s factory sent out a majority of the ice cream consumed during the Civil War.

Fussell began the tradition of ice cream as an American military staple. During World War II, the U.S. Navy produced 10 gallons of ice cream per second for its sailors (Powell 163). Ice cream, though it does not originate from The United States, has become synonymous with the United States. During times of international war, other countries have watched Americans eat the stuff (literally) by the gallons. Even though ice cream exists in dozens of other nations, only in the United States has it become linked to patriotism through its historic military ties, perhaps explaining why America is currently the greatest producer and consumer of ice cream. So not only is ice cream tasty, but it’s downright American!

Powell, Marilyn. Ice Cream: The Delicious History. New York: The Overlook Press, 2005. Print.

Santlofer, Joy. “‘Hard as the Hubs of Hell’: Crackers in War.” Food, Culture & Society: Wilson Web 10 (2007): 191-209. 13 October 2009.

Volti, Rudi. “How We Got Frozen Food.” Invention and Technology Magazine. American Hertiage. Web. 18 October 2009.

Allison for Oct. 20

Posted by Allison Crerie in Uncategorized on October 18, 2009

Walt Whitman craves intimacy. This thought has occurred to me sporadically throughout the semester, but the readings for this week, especially the letters and Ellen Calder’s piece, struck me over and over again with Whitman’s desire for intimacy with any and every one. Now I think it’s safe to say that I know Walt Whitman to a certain extent; here’s what I know for sure:

1.) He is an optimist. I discussed this in my last post and now it has been officially confirmed by Ellen Calder (*pats self on back*).

2.) He desires and is driven by intimacy.

3.) He is, without a doubt, gay. Gay as the day is long.

Of all the other unencumbered facets of the Good Grey Poet’s being, I can only offer inklings and educated guesses, but of these three things I am positive. Since Whitman’s optimism is old news, I will delve into my discovery of the latter two of these certainties.

In his letters, no matter the recipient, Whitman will often begin with some statement like, “it is a comfort to write home, even if I have nothing in particular to say” (42), or, “I have nothing of consequence to write” (107), and then launch into multiple pages of recounting his current conditions and most recent experiences. Long-winded details are to be expected in letters to his immediate family, but his letters to his sister-in-law, Martha, his friend, Hugo Fritsch, and even to his contemporary, Ralph Waldo Emerson, express the same level of intimacy as those to his own mother. His letters, both in their content and quantity, express his eagerness for people to know him; his opening lines of, “oh I don’t have much to talk about BUT,” are a classic sign of someone who has a whole lot to say and desires the full attention and participation of the receiver (we all have a friend who does this). Whitman is not self-centered, however, he puts all this information out in hopes of receiving the same amount back. He impatiently urges his recipients to respond; even to Emerson, some one he’s not all that close with, he says, “answer me by the next mail, for I am waiting here like a ship for the welcome breath of wind” (41). Calder speaks often of the long conversations that would occur in the presence of Whitman, which further convinced me of Whitman as both a hungry contributor and consumer of information. Calder easily shares intimate details of Whitman– specific lines of poetry he would recite, certain words he liked, little sayings of his, etc.– and though we cannot know for certain, I am sure than Whitman could have just as easily shared intimate details about Ellen Calder. Intimacy is in the details, and Whitman is fueled by details. As a nurse, he picked up on preferences of certain soldiers; Morris shares how Whitman discovered that patients with a fever enjoyed the scent of lemons, and would carry around an array of “goodies” to fulfill each unique need. Whitman longs to connect with anyone who will act as recipient, be it a reader he knows personally, a reader he has never met (perhaps one in the year 2009, sitting at her laptop), a close friend, a wounded soldier, or Tom Sawyer, to whom Whitman wants to give something extra special.

No matter what Reynolds’ might claim in “Calamus’ Love,” Walt Whitman was a homosexual. Period. Reading his letters to Tom Sawyer, you would have to be utterly dense to not recognize that Whitman was infatuated, if not in love, with this soldier: “I hope we shall yet meet, as I say, if you feel as I do about it– and if [it] is destined that we shall not, you have my love none the less, whatever should keep you from me, no matter how many years” (57). As Tom continues ignoring Whitman, Whitman takes on a tone of love-sick desperation: “Do you wish to shake me off? That I cannot believe, for I have the same love for you that I exprest in my letters last spring & I am confident you have the same for me” (93). Really, Walt, you think so? Poor guy. What truly set me over the edge were Whitman’s comments about marriage to Ellen Calder. He expresses that marriage is not for him, that he does not envy a man’s wife but envies his children. In this moment, I pitied Whitman. Whitman does not desire a wife, because he cannot intimately connect with women–any woman– but he does crave a family. Of course, having two Dads was not exactly an option in 1865, so here sits Whitman fawning over Tom Sawyer and yearning for a genuine partnership and family that he knows he will never have. It’s no wonder that Whitman’s favorite lines to recite in Ellen Calder’s home were about the agony of unrequited love. Despite all his attempts at intimacy, Whitman will never know in his lifetime the fullest, greatest form of intimacy that he so desperately longs for. What results is a hopeless grasping for connection to all those around him, both inspiring and depressing.

_-_1855_-_Da_front._di_Foglie_d%27Erba.gif)